In Central, age and dryness speak of an unchanging, timeless environment. Yet change is occurring naturally. From time to time, birds and winged insects are blown in from Australia. Among the avian newcomers are the spur-winged plover and white-faced heron, both of which colonised New Zealand from the south through the 20th century and are now common in Central. They will not be the last of the blow-ins.

Change has also been accelerated by human endeavour over the past few hundred years. The tussock grasslands owe their widespread distribution to the fires, deliberate or accidental, of early Polynesians and 19th century European pastoralists.

Maori were here for centuries, making seasonal journeys inland from settlements on the Otago and Southland coastline. They came for rock, notably argillite; for fibre, including Celmisia mountain daisy leaves and the dancing fronds of the ti or cabbage tree; and they came also for prized food such as eel, duck and pigeon, which they cooked on the move.

Europeans did not reach the Otago hinterland until 1853 – five years after the first Scottish settlers arrived in Otago Harbour aboard immigrant sailing ships. Twenty-two-year-old Nathanael Chalmers, with two Maori guides, was the first European to see Lakes Wakatipu, Wanaka and Hawea. Sick and exhausted by the arduous trek inland, he returned to the coastal lowlands down the Clutha River on a raft made of flax and raupo sticks, surviving the gorges and rapids.

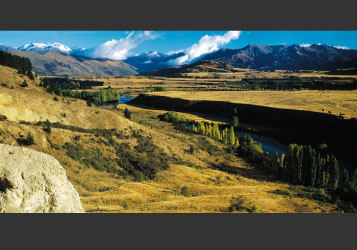

The Clutha Mata-Au, still New Zealand’s mightiest river, cuts straight through the middle of Central Otago from its outlet at Lake Wanaka, draining a main divide catchment stretching from the Haast Pass to the Routeburn. Here, then, is the ultimate landscape irony – a massive river eddying, swirling, sliding and tumbling through the nation’s driest area.

At Lowburn, near Cromwell, the southward track of the Clutha is intersected by latitude 45 degrees south, the halfway point between the South Pole and the Equator. It is a landmark area in more ways than one, for Cromwell is the most inland town in New Zealand and the South Island at this point is at its broadest.

These are heartlands in every sense, natural, physical, human.

That Gilbert van Reenen loves to indulge himself in this landscape is self-evident. His images hum with the region’s natural artistry . . . the sublime lighting and colour, the severe cold, the dry, treeless spaciousness, and the mountain majesty. Few people or human structures intrude into his images, and when they do, they speak of a backblocks landscape and experience, hard and character-building – and highly worthy of preserving.

His images provide an insight into the soul of Central Otago. Through them we commune with the region’s special nature.

Neville Peat

|